BZRK hacked my brain to make me stupider

It’s bad guys. It real bad.

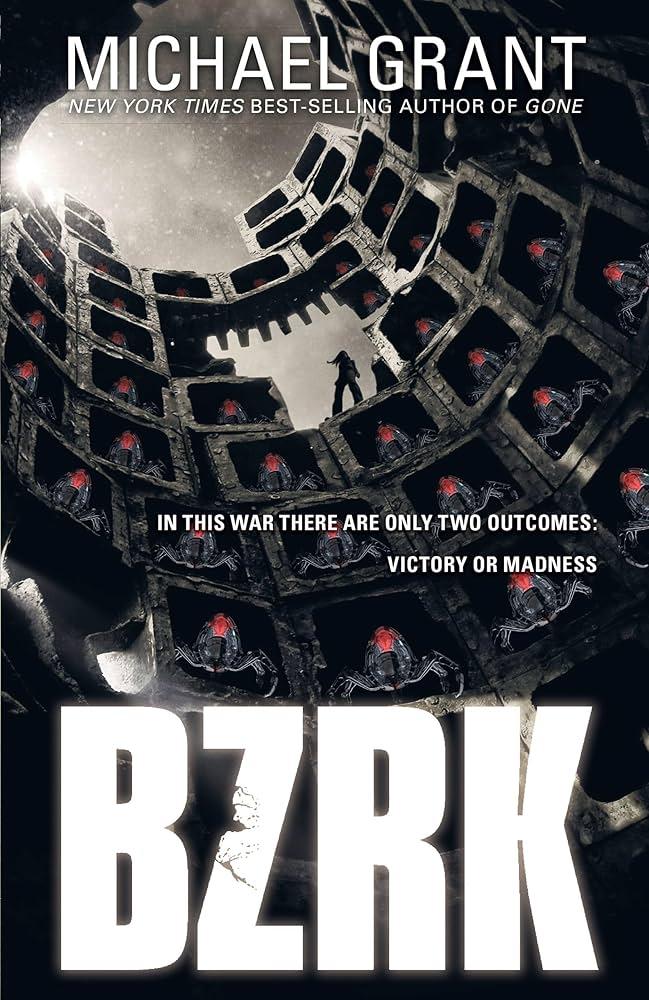

I don’t recall where I was recommended BZRK as a decent sci-fi YA novel, but seeing it at a local Little Free Library, I thought, “how bad could it be?”

It’s bad. Real bad. Superbad, even.

YA fiction as a genre by itself strikes me as such an strange thing. When I was growing up reading, there were certainly age-appropriate books, but the grouping of “YA” didn’t seem to exist just yet. Instead, each book or series just existed in its broader genre, as generic as “fiction” and more specifically something like “sci-fi” or “fantasy.”

From my outsiders view, it seems that after the wild success of Harry Potter, a surge of books and authors provided with an avalanche of content, hoping to hit it big. Some, like the Hunger Games, Maze Runner, or Divergent have made it to the movie adaptation stage of success. Others, despite their quality like Brian Jacques’ Redwall series, struggles to ever make the leap. It seems to me that publishers and authors have taken the approach of flooding the zone, trying to fill the book-series-to-film-series pipeline. I suppose it’s like getting paid to write spec scripts.

BZRK imagines a world in which nanobots and biological counterparts dubbed “biots” can be used to enter the human body to monitor what the person sees and even “rewire” their brain to do what the hacker, or “twitcher,” wants them to do. Two secret organizations battle for control of the world, with the antagonists wanting to unify the world into a totalitarian utopia of singular thought, and the protagonists fighting to maintain everyone’s freedom.

It’s interesting how the use term “twitcher” overlaps somewhat with the rebranding of Justin.tv into the video game streaming service Twitch. Most of the twitchers come from the gaming community and characterize their espionage and clandestine operations as “a game.” Their general attitude also comes from popular depictions of “hacker” culture, somewhat like the characters portrayed in Hackers. Twitchers will adopt a nom-de-guerre similar to a username/handle, with the protagonists collectively adopting the theme of famous artists who either went insane or committed suicide like Sylvia Plath, Vincent Van Gogh, or Vaslav Nijinsky. The theme is somewhat macabre, and a bit insensitive to struggles of mental health by using it as a token theme in this way. Like a lot of the book, it screams “edgy teenager.”

Most of the characters and plot points are alright for a YA novel, though there is an undercurrent of misogyny with the role and characterizations of female characters. There are several women that are “wired” by twitchers to have romantic feelings for male characters, with one outright being a sex slave to one of the antagonists. The author doesn’t seem to have much to say on this topic other than to say that “it’s bad,” and unsurprising for an author of his generation, tends to mention sexual and romantic attraction from a male perspective towards female characters. The most extreme violence happens to female characters, which also seems like a pattern. Male characters experience violence as well, but it’s the female ones that are murdered and maimed at a higher rate than the male ones.

I did spot an interview with the author where he bristles at a question regarding the diversity of his characters, to which he seemed to respond quite defensively that he does make a strong effort to include diverse characters in his work. In BZRK, at least, it seems quite obvious to me that it’s all token diversity and liberal use of stereotypes. No character really embodies their traits, and the lack of the ability of the author to make characters distinct from each other cements this problem.

Sure, there are Black, gay, South Asian, East Asian, and disabled characters all over the book, but none of those traits inform the behaviors of the characters. Worse, the disabled characters are either evil, institutionalized, or mercy-killed, another indication the author doesn’t really understand the lives of people with those backgrounds or how to treat them with humanity. It’s token diversity at best, and it’s a shame that a YA novel doesn’t do better to set a good example for younger readers.

The novel exhibits a strange characteristic where poor writing pervades the first 40% of the book, while the latter 60% exhibits fewer but different problems. It’s almost as though the book was written by multiple authors, or that an editor focused on the action parts and less on the establishing sections.

I returned this one back to a different LFL, and, at least of this writing, it’s been sitting on that shelf for months. I’d recommend you leave it there if you should ever find it.